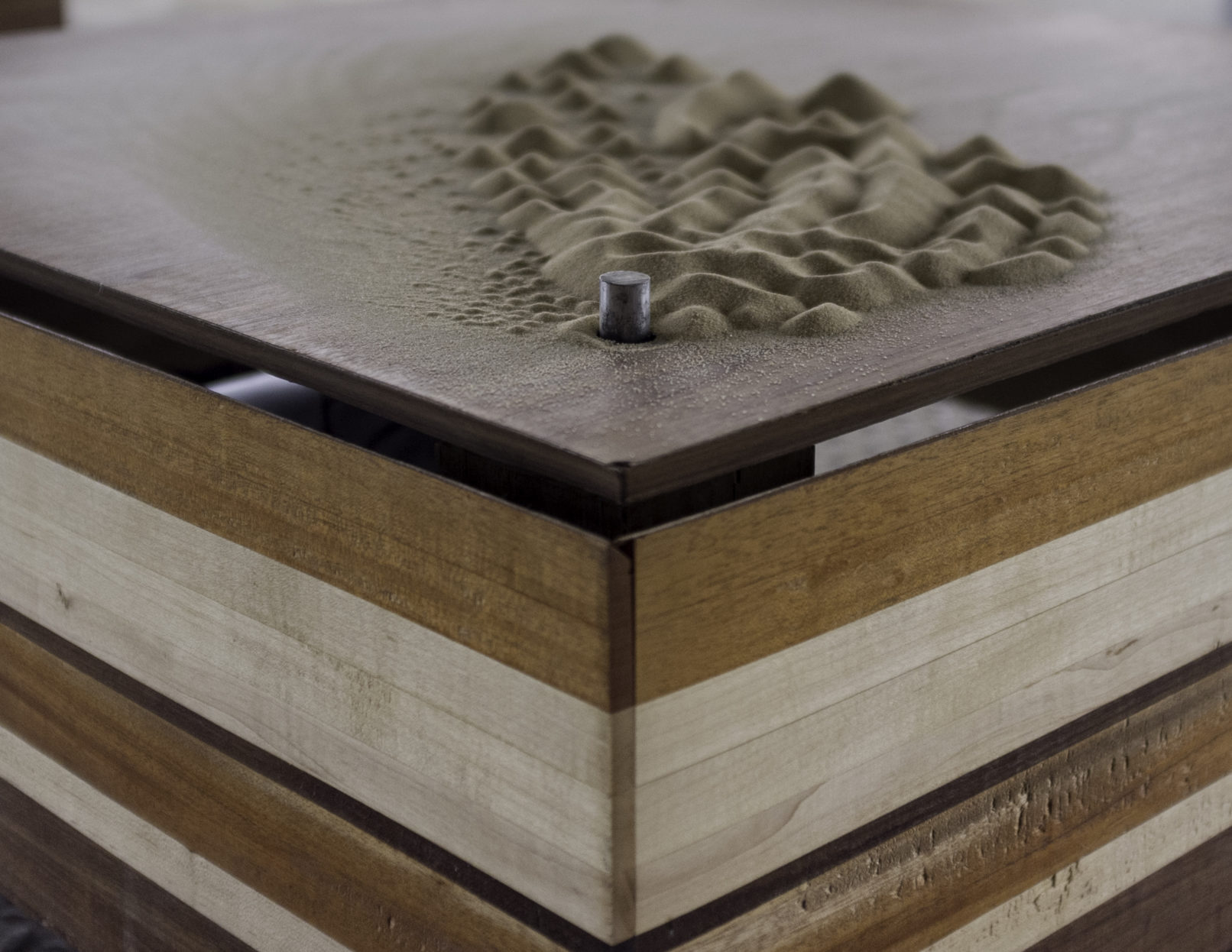

Petrosyllabic Resonator II

Frustrated by Thomas Wolfe’s warning about the peculiar unreachability of home, my cyclical thoughts first crystallized into a song about slippage and pyschogeographic silt.

The song uses simile to recast unremembered years as earthy accumulations under a geologist’s hand lens, wherein stacks of stone may be read for their melodramatic revelations. The Earth is a ceaseless churning machine whose mechanics of writing and unwriting history may be repurposed at the scale of human lives and stories. Within this framing, our oral repetition of some anecdotes and suppression of others takes on a distinctly sedimentary quality

The cyclic retelling is not lossless – causing aberrations and chimera to emerge. These hybrid memories become laminated into stratigraphic columns of self-myth. This ductile skin of stories must rest upon some kind of armature, and mine is largely cartographic. “The truth is,” wrote Eudora Welty, “Fiction depends for its life on place. Location is the crossroads of circumstance, the proving ground of ‘What Happened? Who’s Here? Who’s Coming?’”

As our instants inevitably evaporate, their coordinates wander away from the realm of tangible things, and must instead be plotted within the domain of metamorphic memory. In protest, I devised my own churning machine to correct for these distortions by using the spoken remnant of places remembered as a catalyst for the formation of new landscapes.

–

The Petrosyllabic Resonator is an open wooden box with a magnetically levitating sounding board held loosely aloft by neodymium rings encircling aluminum posts. Bolted beneath the sounding board, four large transducers convert audio signals into tremors. Above the sounding board, these tremors reshape piles of sand into ever evolving micro-terrains.

Within the box, an amplifier adds appropriate heft to the electrical pulses it is fed. Upstream along the wire, a turntable stylus tracks acetate grooves, converting minuscule excavations into a feeble, yet dynamic current.

At 33rpm, the grooves provide just enough space for 7 minutes of audio. Those seven minutes were cut into the acetate by a specialized lathe cut in one of the many basements of Columbus, OH. The audio source was digital file that I had recorded in a friend’s home studio the night before.

That night, I had spoken for more than 3 hours continuously into a microphone while my friend drifted to sleep. I spoke my most tenacious memories of home, joys and terrors all at once. In the morning, we snipped away at the waveforms until all stories had been arrested into 7 kaleidoscopic minutes.